Scenes and images from a city in transition.

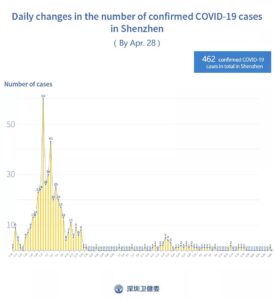

It’s been roughly six months since Shenzhen introduced measures to control the spread of COVID-19. Statistics from the Shenzhen Health Commission (卫健委) show that the highest number of cases occurred at the end of January and early February. There was a second wave that coincided with the return of residents after the Chinese New Year’s holiday. Indeed, the city has emphasized the difference between “locally transmitted” and “imported” cases. As of July 19, 2020, the city had a confirmed total of 462 cases, while the most recent case was reported on April 28, 2020.

Daily changes in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Shenzhen, statistics from the Shenzhen Health Commission, circulated via the EyeShenzhen WeChat account.

In this post, I’m offering scenes and images from these past months to give a sense of how the city has gradually come to terms with the pandemic as well as what we have learned about society now that many have taken off their masks.

On January 27, 2020 I rode the Shenzhen metro, where I passed through an internal checkpoint that had been set up for the 2011 Universidade—the World University Games, decommissioned, and then reactivated after the Xinjiang crisis crossed borders into Yunnan during the 2014 Kunming attack. It was the third day of Chinese New Year and friends had begun visiting each other to offer New Year’s wishes. Ahead of me another traveller was arguing with security guards because he would not be permitted onto the subway without a face mask. I had worn one because I planned on going to Hong Kong for the day. As I slipped past him, I overheard him saying that he needed to get to the train station. They replied that he wouldn’t be allowed on a train without a face mask either. Clearly frustrated, he responded that if people needed to be masked in order to use public transportation, then Shenzhen Metro had a responsibility to provide those masks. On my ride, four clips from the national anti-terrorism animation looped on the metro media screens. The antagonist of all four animated videos was a Middle-Eastern man (recognizable by his thick mustache), wearing a black baseball cap, black jacket, black sunglasses, and black pants. I wasn’t sure if there was a connection between anti-terrorism and vigilance about public health, but at Shenzhen Bay, I crossed the border without incident. I enjoyed the day in Aberdeen, Hong Kong, where roughly half those I saw were wearing masks, and returned to Shenzhen.

A metro security guard checking a passenger’s temperature, early February.

Screenshot of the anti-terrorist video clip, which can be viewed at https://v.qq.com/x/page/x0859rcg2t5.html.

Shenzhen was on lockdown during February and March. Our housing estate has two entry gates, where our security guards set up stations to record who entered the compound, when, and their temperature. Every four or five days during the lockdown, my husband and I went grocery shopping. Small markets had been closed, but larger markets were open for limited hours. Stores had been sealed off all except for designated entries, where security guards had set up stations to prevent unnecessary people from entering, to record who was entering, when, and their temperature. On shopping days, we put on masks and walked to a large market about a mile from our apartment. Unless one worked for the government or an essential industry there was no place to go and so most of us transitioned from a prolonged Chinese New Year’s holiday into the lockdown, moving between our residence and the store. On the way, we passed emptied buses, maybe a car or two, and pharmacies, which were the first small stores to open. In a nearby park, an older practitioner of tai chi would sometimes hang his mask from a tree branch as he moved through daily exercises. Delivery boys on mopeds darted through the streets, the only ones allowed past the gates.

Entry to my housing estate, mid-February.

Grocery shopping, mid-February.

Empty streets and empty bus, mid-February.

People had begun returning to the city in March and by April, restaurants opened. When we went to a restaurant, a server recorded our names, contact numbers, and temperatures. However, by the end of the month, the city had begun holding unofficial, small-scale events. On April 25, Handshake 302, an art space and initiative, held its first public event at the Xichong beach, where we had co-curated the 2019 UABB Yantian sub-venue exhibition. The exhibition had opened on December 22, 2019, and then, like the rest of the city, went on extended shutdown after Chinese New Year’s. The city and its districts had spent millions on the main venue at Futian Station and nine sub-venues—Shatoujiao, Bao’an, Qiaotou, Dapeng Fortress, Xichong, Banxuegang Hi-Tech Zone, Guanlan Ancient Market, Guangming Cloud Valley, and the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone. The sites succinctly mapped Shenzhen’s du jour vision of its future self: renovating manufacturing sites (Shatoujiao, Bao’an, and Qiaotou), investing in cultural sites (Depeng Fortress, Guanlan Ancient Market, and Xichong), and upgrading its high-tech and AI adjacent industries (Banxuegang, Guangming, and Qianhai). However, instead of attracting Shenzhen residents to explore the city, throughout the lockdown and after, the sites remained empty. Curators organized online activities, including talks, videos, and iPod broadcasts. As the city gradually reopened, the exhibits were quietly dismantled, introducing residents to places in the city that many had never visited and, without the incentive of a city-level exhibit and associated events, might not take an hour-long subway ride to another district.

“Threads of Time,” Handshake 302 embroidery workshop, Xichong, April 25, 2020.

“Candy House,” Handshake 302 story-telling workshop, Xichong, April 25, 2020.

“Puppets on the Beach,” Handshake 302 workshop, Xichong, April 25, 2020.

The late April and early May flourishing of offline activities signalled more extensive reopening of the city. On May 6, 2020, Handshake members and our families went to Baishizhou to have dinner and drinks at Peko, a microbrew pub that had opened in 2013, the same year that we had moved into our art space in Baishizhou. As part of the demolition and urban renewal plans for Baishizhou, Handshake 302 had been evicted from our space in August 2019. Businesses like Peko, however, had been allowed to remain open until further notice. That said, the pandemic seriously impacted the ability of Baishizhou shops to stay open. Like housing estates and malls, urban villages had been cordoned off during the lockdown. Baishizhou, for example, had only two entries, where security guards prevented unnecessary people from entering, recorded who was entering, when, and their temperature. These measures reproduced those throughout the city. Unlike housing estates and malls, however, urban villages are multi-use neighborhoods, comprised of “handshake buildings”—so-called because they are close enough for neighbors to reach out their windows and shake hands across narrow alleyways. In Baishizhou, the developer took advantage of the pandemic to block off entire blocks of buildings. Peko was located on Baishizhou’s Food Street, which had been set up in the alley between repurposed factories. That evening it was challenging to find an entrance into the area because although shops near Shennan road were still open, further inside the village many streets had been boarded up, isolating entire blocks in anticipation of scheduled demolition.

Built in the 1980s, this first generation factory was cordoned off as part of the demolition and relocation (拆迁) stage of urban renewal, Baishizhou, May 6, 2020.

Shahe Road, the main commercial street of Baishihou, May 6, 2020.

Looking from the Baishizhou Food Street toward CRC Huaruncheng (华润城) in neighboring Dachong, which was redeveloped in the 2010s.

As I write, COVID-19 prevention videos are playing on loop in the metro, health announcements have been wrapped around the barriers that separate construction sites from the city, and there are temperature and “health pass” checkpoints at every business and building, subway station and urban village. Indeed, Shenzhen exudes a sense of coordinated movement. Cars and trucks flow through the city’s wide roads, its subway system continues to expand underground, spreading like banyan tree roots from central Futian, and people rush about the city, working, shopping, and hanging out. It’s as if the pandemic has passed. And yet, there are signs that not only are we still in transition, but also that we are transitioning to a different kind of embodied regime.

First, real space has been further channelized. Before the pandemic, online ordering and home delivery service was an important part of everyday life. However, during the lockdown, online dependencies increased as people only moved between several designated spots, with few options for wandering off to window shop or hang out in a park. Second, online meetings and events have become commonplace. Before the pandemic, there was a preference for events—especially lectures, movie screenings, and exhibitions—that took place in unique settings, and provided unique spatial branding. However, today, many organizations have developed online branding strategies, including live streaming to create and maintain their social presence. What’s more, at a more individual level, there have been online photo-galleries, where people upload images on a shared theme, online talks where people listen to and interact with a guest speaker, and even more online gaming than usual. In other words, many young people who were already online see the lockdown as a chance to intensify their online friendships, which they agree were often less stressful and more rewarding than face-to-face interactions.

Third, a masking hierarchy seems to be emerging. In official public spaces such as the metro and public buildings, masking is required. In shopping malls and other semi-public spaces, workers must be masked, while customers wear masks to enter the building, but can and often remove the mask once inside. Outside, there is a mix of people wearing and not wearing masks. What this choice means case-by-case is open to debate. Smokers were the first to pull their mask down below their mouths so they could light up, while it seems that children wear masks because their parents require them to do so. What is clear, however, is that our new awareness of physical vulnerability has entwined with increasing dependence on virtual connections, a conditioned that is figured by the color-coded passes we carry in our cellphones. Green means we have been in Shenzhen long enough to safely enter any building, yellow means that we are on probation and could be denied entry to public spaces, and red means the carrier—in all senses of the word—must be quarantined.

Handshake 302 “Zero Waste Art,” workshop, July 4, 2020.

Beach, Shekou, July 19, 2020.

Artist-ethnographer Mary Ann O’Donnell has sought alternative ways of inhabiting Shenzhen, the flagship of China’s post-Mao economic reforms. O’Donnell creates and contributes to projects that reconfigure and repurpose shared spaces, where our worlds mingle and collide, sometimes collapse, and often implode. Ongoing projects include her blog, “Shenzhen Noted” (since 2005) and Handshake 302, an art collective which was established in 2013. She co-edited Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City (University of Chicago, 2017) and her research has been published in positions: east asian cultures critique, the Hong Kong Journal of Cultural Studies, and Made in China.