The relative success of Japan in containing COVID-19 reveals gaps in the common narratives about ways to control the spread of the virus, and the role of the state writes Sakiko Fukada-Parr for Pandemic Discourses.

The relative success of Japan in containing COVID-19 reveals gaps in the common narratives about ways to control the spread of the virus, and the role of the state writes Sakiko Fukada-Parr for Pandemic Discourses.

After 2 weeks of quarantine in Tokyo, I managed to get to my destination, a nursing home where my mother lives. This facility has not had a single case of COVID-19, despite the advanced age of the residents; my mother is 99 and is by no means the oldest.

This is not surprising. It is consistent with the low number of cases and deaths in Japan – just 92,000 cases and 1,661 deaths as of October 17, 2020. In a country of 126 million, this comes to 13 deaths per million. That is not as low as 0.3 in Taiwan or 5 in New Zealand but the number still pales in comparison to the mortality rates in other high income countries such as the US (676 per million) or Germany (117 per million).

What explains this outcome? Japan does not fit easily into the stereotypical explanations that are offered for other countries with low numbers, such as authoritarianism that makes harsh lockdowns and social distancing measures enforceable, or strong political leadership that inspires citizens to join a national effort. No one I have talked to—mostly family and friends of various political persuasions—had anything remotely positive to say about the prime minister or the government in their handling of the pandemic. As one friend said, “the government is incompetent about everything.” No matter that the situation is more dire in the US and Europe.

“The dominant narrative in the media does not give much attention to public health education and information, contact tracing, community social support for isolation, quarantine, or border control. These are not seen as priority measures for containing the pandemic. Yet they have long been core elements of a standard approach to infectious disease control.”

The Western press gives only occasional attention to Japan’s experience, presumably because there is no easy lesson to be drawn. It belies the widespread belief in the model followed by countries such as New Zealand, South Korea, China and others that controlled the spread: strictly enforced lockdown and widespread testing while awaiting the release of a safe and efficacious vaccine. Japan did not implement a hard lockdown and testing remains relatively limited. Even under the state of emergency the government did not require but respectfully requested the cooperation of citizens to practice social distancing, work from home, wear masks, and wash hands. Government has recently started gradual reopening, while advising “avoid the 3C’s,” the WHO formula: closed spaces, crowded places, and close contacts. Primary and secondary schools are open, and a campaign has even been launched to promote travel in the interests of helping the (domestic) tourism industry. The roads are nowhere near as congested as in pre-pandemic times, the restaurants do not have waiting lines but life looks “normal,” with shops, schools, offices mostly—though not fully—open.

Perhaps it is precisely this enigma that we can learn from. Perhaps the experience of Japan can reveal gaps in the common narratives about ways to control the spread, and the role expected of the state. One such gap would be the importance of public health services, particularly at the local level. The dominant narrative in the media does not give much attention to public health education and information, contact tracing, community social support for isolation, quarantine, or border control. These are not seen as priority measures for containing the pandemic. Yet they have long been core elements of a standard approach to infectious disease control.

Could this be a major factor that explains Japan’s relative success in containing the virus? One can’t but notice that masks are universally worn, and worn correctly, readily available at a fraction of the price in the US, and are of high quality with a “made in Japan” label prominently displayed. Masks and hand sanitizing appear to be universally respected, although there is no enforceable state mandate. These practices are commonly attributed to “culture,” which serves to dismiss them as a strategy that could be replicated elsewhere. But recall that disseminating information is an important function of local health services. Like everyone else in the world, Japanese people do not enjoy wearing masks. We were taught to do so as a public health measure, something I remember from my kindergarten and primary school days in Japan. In the same way, Americans wear seat belts and mostly refrain from smoking. This behavior is not part of tradition but a result of massive public information campaigns waged by civil society activists. Social norms can change, particularly in response to crises.

Contact tracing, and associated case identification, isolation, testing, care, and quarantine, appears to be a central element of the national strategy. According to the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, “In the absence of reliable therapeutic agents and vaccines, the only way to proactively implement preventive measures is to collect infected person information, including behavioral history, identify close contacts as accurately as possible, and prevent infection.” Moreover, the process builds on a well thought out epidemiological strategy, and institutional capacity.

Most countries conduct “prospective tracing” to identify individuals who have been in contact with a positive case and advise them to isolate in order to avoid further transmission. However, Japan also conducts “retrospective tracing” to identify the source of transmission. According to Dr. Omi, the chair of the Prime Minister’s Advisory Panel on COVID-19, 80% of the positive cases do not go on to infect others while the remaining 20% infect many others, becoming “super spreaders” and creating “clusters.” Retrospective tracing aims to identify the clusters and those who came in contact with them. This seems to be a more sharply targeted approach that is aimed at zeroing in on the sources of spread.

Japan has a well-developed social infrastructure for implementing contact tracing, and subsequent testing and isolation. To begin with, the country has a system of hundreds of public health centers, trained personnel and a history of dealing with infectious diseases. The system originated in the 1930s to contain TB. A recent article in Asia Times described Japan’s method of contact tracing as “old but gold.” The health centers act as “gate keepers” by prioritizing testing and preventing hospitals from becoming vectors of transmission. Given that Japanese homes are very small by international standards, quarantine is not always an easy option for those who are exposed, or test positive for COVID-19 but are not ill enough to require hospital treatment. Local governments have set up special isolation facilities. One newspaper article describes a new isolation facility being built by a local authority that implies a human-centered design. Units have direct access from the outside, while some allow families to isolate as a unit, and allow pets.

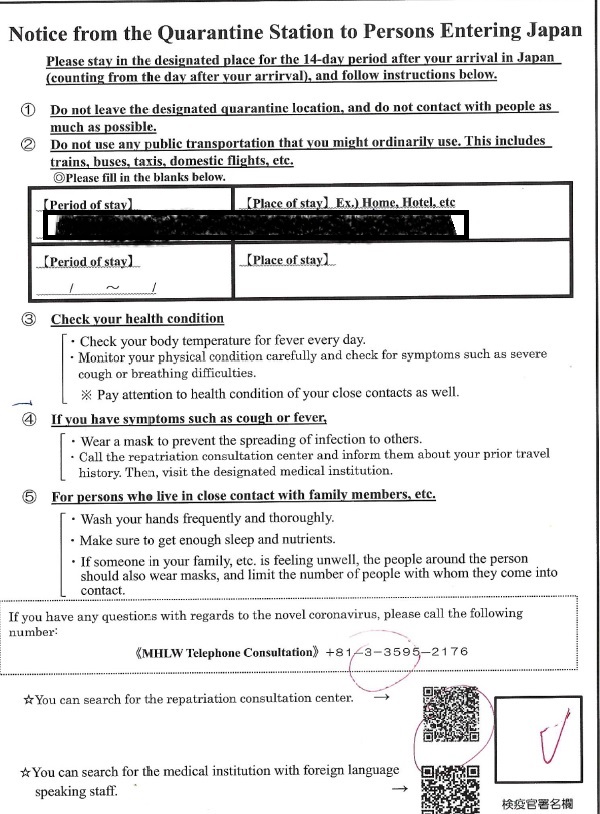

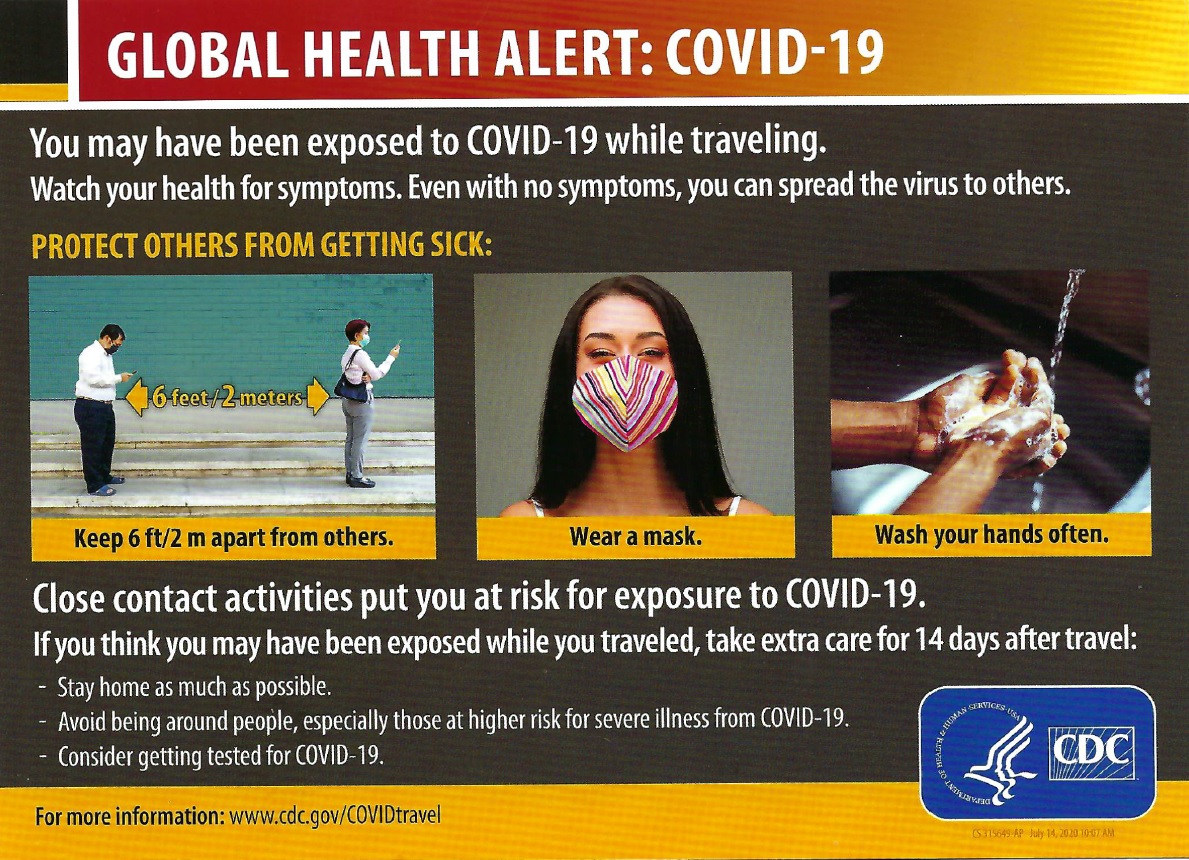

Another important element of infectious disease control is managing the national border. Not only has Japan prohibited entry from a list of 159 countries, those (mostly Japanese nationals like myself) who land must go through a very strict quarantine process. The Ministry of Health has taken over the entry protocol. Before proceeding to passport control, we go through quarantine services where we are tested, mandated to provide contact information, given a pep talk about proper behavior, and required to quarantine for 14 days with an emphasis on not taking any form of public transport including taxis. We are advised to monitor our health and given a phone number to contact in case we begin to show signs of symptons. This contrasts with the lack of health quarantine protocols when entering the US and many European countries. (See health cards given out at Narita airport and at Newark airport.)

Another important element of infectious disease control is managing the national border. Not only has Japan prohibited entry from a list of 159 countries, those (mostly Japanese nationals like myself) who land must go through a very strict quarantine process. The Ministry of Health has taken over the entry protocol. Before proceeding to passport control, we go through quarantine services where we are tested, mandated to provide contact information, given a pep talk about proper behavior, and required to quarantine for 14 days with an emphasis on not taking any form of public transport including taxis. We are advised to monitor our health and given a phone number to contact in case we begin to show signs of symptons. This contrasts with the lack of health quarantine protocols when entering the US and many European countries. (See health cards given out at Narita airport and at Newark airport.)

I am not an epidemiologist. Perhaps Japan will be hit by a major wave as people begin to go out more. These thoughts are not based on a scientific survey but are casual observations of a Japanese New Yorker in Tokyo on a short family visit. The point is to ask why the dominant narrative pays so little attention to the role of local public health services. As the pandemic persists, all attention is directed to the promise of a vaccine to save us. We forget that vaccines have not always been the “solution” to the containment of epidemics (Spanish flu? HIV/AIDS?). Even when a vaccine is available, infectious diseases are not totally eradicated, at least for decades (TB? Polio?). We need to be mindful that behavior change will always be an essential part of controlling – and living through – epidemics, and that cannot be achieved without effective public health services. Their neglect is not only in the dominant pandemic discourses, but in the budget priorities of countries. The trend around the world has been a defunding of basic public health infrastructure. As Anne-Emanuelle Birn pointed out in her 2005 article in The Lancet, “transcending technology as a public health ideology” is a key challenge, not just then, but even more in our present pandemic.

Sakiko Fukuda-Parr is the Director of the Julien J. Studley Graduate Programs in International Affairs and Professor of International Affairs at The New School, where she currently teaches a course on Global Pandemics. She is also a co-editor for Pandemic Discourses. Her teaching and research have focused on human rights and development, global health, and global goal setting and governance by indicators. She was in Tokyo recently for a family visit.

(On November 12, the India China Institute hosted an event on the factors that have shaped successful responses to the pandemic in Japan and other Asian countries. Watch the video: “Exemplars in Global Health? Comparing Asia’s Many Responses to COVID 19”)