An Iranian perspective on the impact of COVID-19 on collective mourning published originally by Pandemic Discourses.

In Iran, and perhaps in many other Muslim countries, on the days after the burial ceremony, families and acquaintances usually have three more gatherings. One on the third day, then one on the seventh day, and then a final gathering on the fortieth day. On each of these significant days, part of the mourning ends and the pain decreases as people grieve together.

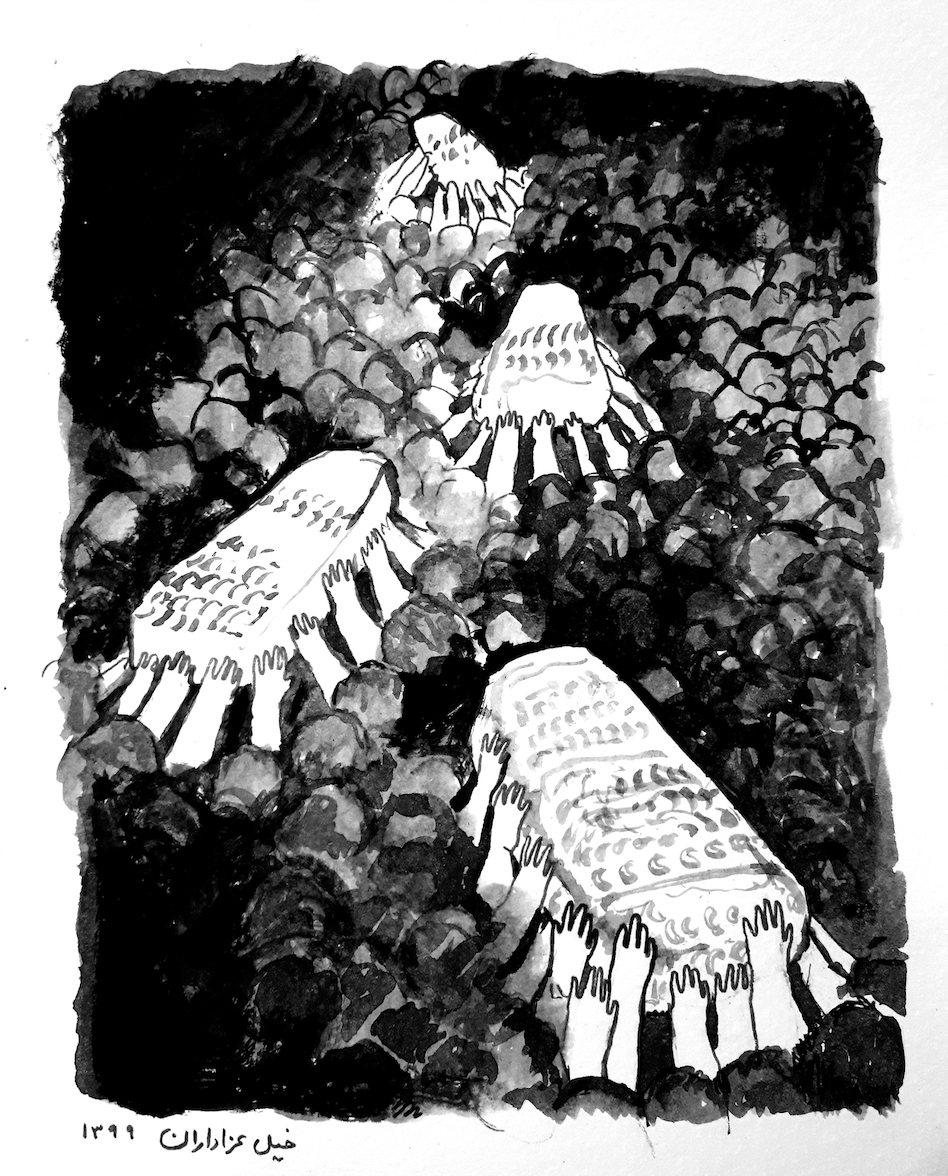

This sequence of days after the funeral gives mourning a duration that allows the crowd to fully experience the tragedy in a collective catharsis that transforms the gathering into a new form of community. Perhaps this is why mourning in the Muslim world is linked to the history of political demonstrations and protest, and the prevention of mourning ceremonies is associated with the history of the suppression of popular forces. In the months leading up to the Revolution of 1978, the frequency of mourning ceremonies became one of the main drivers of mass mobilization. The most radical slogans were chanted on the third, seventh and fortieth day of mass mourning and were dedicated to martyrs who died during previous demonstrations. These demonstrations transformed individual anger and despair into new political forms. Mourning inherently carries a political legacy, and every single moment when it becomes possible to emancipate this heritage, mourning turns into a protest.

In the time of this pandemic how can we sustain the duration of mourning in a year when we keep counting deaths? How shall our lives, now deprived of this customary duration of mourning for our dead, return to any form of normalcy?

Perhaps it helps to ask what exactly happens during the mourning ceremony that allows the mourner—who experiences enormous vulnerability at the moment of loss—to discover a new strength? Her vulnerability is exposed to the public without any mediation, without any false representation, and this can become power itself. In a world that seeks power in an individual invincible hero, mourning is a crowd of non-heroes who can question the structures of power that have been formed in their absence.

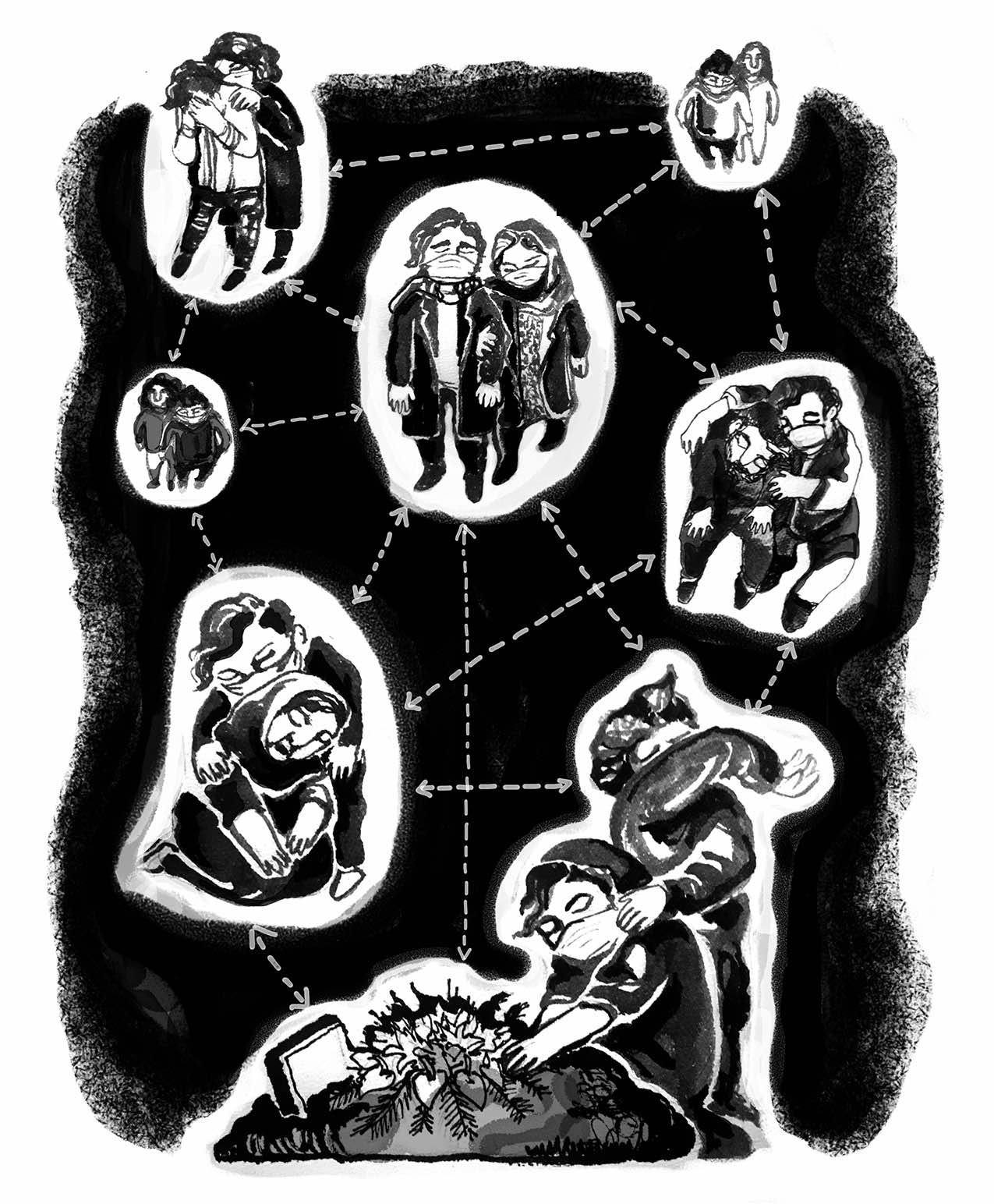

The moment of breaking into tears on the shoulders of an acquaintance with whom we are not normally intimate, the complete manifestation of collapse, inevitably leads to the creation of a new system of forces.

Death without a collective mourning rite—for those who died of the virus or for other reasons—was perhaps the most bitter experience of the past year. Especially for those people who are used to opening their homes to friends and acquaintances to come in and cry on each other’s shoulder. Now these homes are closed and a limited number of residents are mourning inside.

Isolated Funeral, October 2020

How many houses in my neighborhood have experienced this curtailed mourning behind closed doors? How many houses in Tehran have sheltered isolated mourners inside? How many houses in Iran and how many houses in the world of this pandemic? Other than through the words I read from my friends and family, how can I share in their mourning? This is perhaps the main question I’ve been asking myself everyday in Autumn 2020.

Meanwhile, the media portrays countries competing in disaster management. Still hotly debated, numbers are compared as the arcs of the graphs go up and down. It seems that social media has taken away our ability to focus even on the grief of loss. Now the debate has shifted from disaster control to vaccine discovery, but mourning for the dead seems to have shifted to another time. But when will that time be?

According to the Iranian calendar, which is a solar calendar, this year, the year of the pandemic, is 1399. The coincidence of this apocalyptic situation with the last year of a century has led to some common refrains in daily conversation, expressed in different ways but with the same bitter humor, different narrations about the finishing of an old world at the turn of a new century.

In the past year, the most beautiful words, the most accurate sentences with shocking obsession for fidelity to the truth, were written in the language of mourners who lost their mothers, fathers, uncles, brothers, sisters and relatives but could not partake in the usual collective mourning process. It is as if they were trying to pull this epidemic death out of everyday numbers and statistics and link it to the history made by these people and their role in shaping the great political and social events of their time as ordinary people. Sentences that seemed to be uttered in the absence of crowds—normally used in response to the loss—were now supposed to replace the crowd in a different way.

“My grandma, her hands were strong. She was holding your head on both sides with her hands, as if to make everything that was shaking in your heart return to its place. She used to say: ‘Madar Jaan, pray for the root of oppression to be uprooted and if you are scared, tell the water first…’”

“Baba, in a century of your life, you have always pursued your ideals above all values. You told me that your job (the first generation of engineers in Iran) was to turn on the lights in every person’s home. You turned on the lights of thousands of houses, their lights illuminated our way.”

“Madar Jaan belonged to a generation of ordinary Iranian women who introduced modernity into their daily lives and the lives of their children with delicacy and precision. Without destroying the past, she paved the way for the better and comfortable life of her children. Women who themselves became a valuable bridge between heterogeneous worlds so that we could cross safely.”

“My aunty was one of the first apartment dwellers in Tehran. She and her teacher husband had pre-purchased an apartment from a construction company in the Shahr-e-Ara neighborhood. They later forced the engineering company to plant greenery and trees in the neighborhood by forming a pre-purchasers’ union.”

In these lines we could read the social history of the city and its people, among many other untold and unwritten stories. They were formulated and written down for the sake of giving words to sorrow.

Funeral of Mohamdreza Shajarian, September 2020

Historical events—in which time is split into a before and after and there is a huge gap in between the two—make us link peoples’ deaths to the time they lived in. A grandfather who saw the Constitutional Revolution, a grandmother who remembers the day of the CIA coup against the elected Prime Minister of Iran, a father who experienced prison before and after the revolution, or a mother who gave birth to one of us during the war. In the last year of the century, we have lost many from this generation, due to the virus or old age, and what all these losses have in common is the lack of collective mourning ceremonies. We could not attend any of their funerals, and we had to remember their history from a distance.

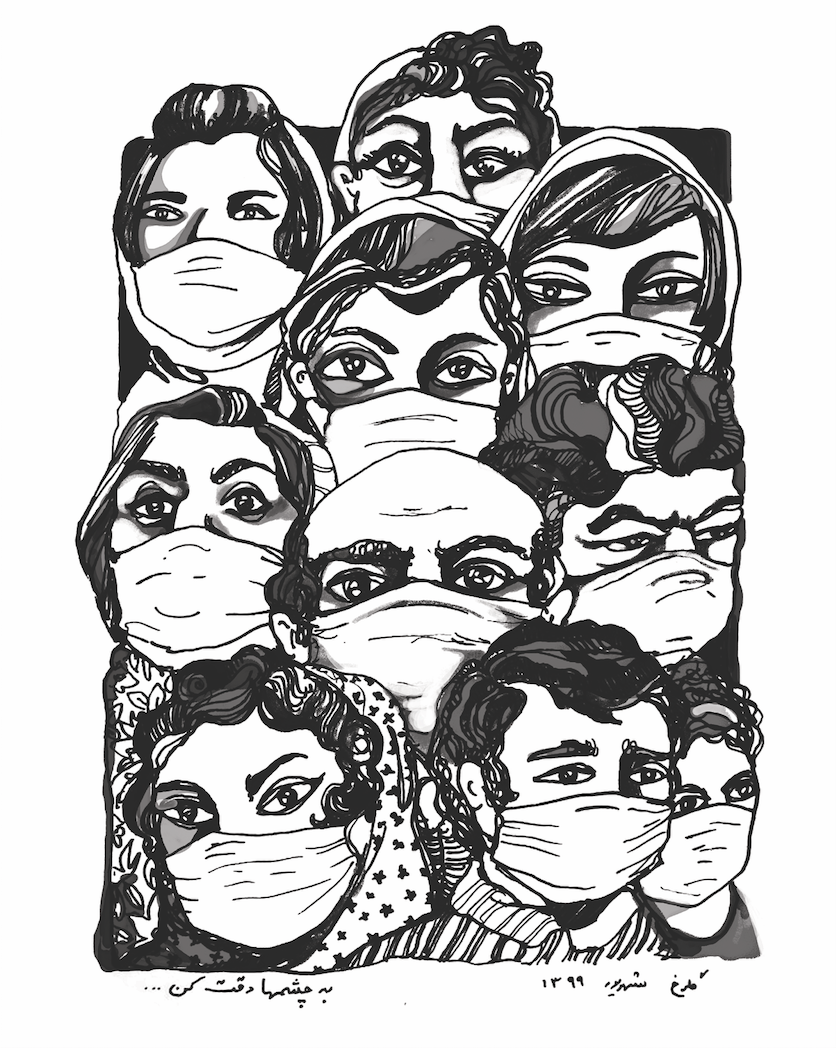

Look at Their Eyes Carefully, August 2020

Beside more than fifty thousand people who have died in Iran from the virus, this year is also the year in which our parents and part of the previous generation who witnessed and built (among other great historical events of the last century) the revolution, are slowly leaving us and their historical and incoherent oral memory is slowly disappearing with them.

Other than a year of the pandemic and the last year of the century, what else is on our collective calendars?

February this year marks the forty-second anniversary of the revolution. Iran was in the process of opening its doors to the “world” through a deal with the west in 2015 but that deal disintegrated after the withdrawal of the United States in 2016 and subsequent waves of sanctions. Iran no longer has its revolutionary independence to stand against the world’s economy, nor has the possibility of joining the global economy. This is a condition that has already been enjoined on more or less all the countries in the region, from which military states have usually emerged. Triggered by the shattered economy and the tripling of the price of gasoline, the 2019 uprising that erupted mostly in big cities’ suburbs, crashed brutally. Since then, workers, teachers, and student unions continue to live under heavy security. The prices of consumer goods are continuously rising, and it seems pointless to even be surprised by the daily fall of the Iranian currency.

What do we see on the horizon? For those who, like me, were born in the early years of the revolution, it seems that the crisis of this collective history has found significant and strange harmony with our personal history. The generation that was brought into this world with revolutionary hope is now moving into its middle-age crisis, with at best a vague future on the horizon.

Mourners, December 2020

Maybe that is why, at the peak of the second wave of pandemic, it has become difficult to think of a world outside of our own body, home or neighborhood, as we have turned to the smallest version of ourselves. In such a foggy situation, the only image that illuminates the horizon for me is that of collective mourning. A crowd of mourners who conquer the spaces and time with the sound of sorrow. Sorrow is the revitalization of the interconnected emotional capillaries of our numb collective body, which, if connected, will allow fresh blood to pass through, so to shape a new calendar after the old has completely collapsed. A history that seems to be visible and narrated only after the complete decay of an era.

In the early days of 2021, I wish nothing but a collective mourning for our virus-stricken world.

Golrokh Nafisi

Jan 2021 Tehran

Golrokh Nafisi is a children’s book illustrator, animator, and contemporary artist born three years after the Iranian revolution in Isfahan, Iran.