Betti Marenko and Jilly Traganou, co-editors of “Design in the Pandemic: Dispatches from the Early Months,” together with Barbara Adams, use a design perspective to discuss how inventive and localized strategies around the world emerged to handle the challenges posed by COVID-19. This interview was originally published in Pandemic Discourses.

Mark Frazier: Congratulations on the print and online publication of the special issue of Design and Culture “Design in the Pandemic: Dispatches from the Early Months.” What does a design lens add when looking at the pandemic?

Betti Marenko: We were drawn by the huge amount of responses to the issues raised by the pandemic that we could see occurring at multiple levels, and in many different circumstances. Even more, we became interested in drawing out the clear sense of the potential that design practices, interventions, actions and experiences could manifest in the specific time frame of March-June 2020. We wanted to use this moment to present a snapshot of the pandemic response seen through the lens of design capacities and through a design sensibility of intervening in processes and practices in one’s own immediate environment. This special issue became a window for highlighting plural ways of designing (rather than Design) that could express various modes of inhabiting one’s own individual and collective environment. This is particularly important as the pandemic induced a state of heightened economic pressure, exacerbation of inequality, and drastic uncertainty. We also wanted to shed light on neighborhood mobilization, frontline activism, community solidarity, and local levels of rebuilding social fabrics.

Jilly Traganou: I think it is best to clarify that when we use the term “design” we mean a broader realm of material and affective expression and action that includes engagement with objects, spaces, visuals, and materiality in macro and micro levels. We also look at designing as configuring or assembling things, and how these processes occur both through the professional expertise of those trained as designers, and in the work of the everyday designer. And as Betti said above, we also mean a sensibility that pays attention to materiality both as a phenomenological experience and in the understanding of matter as a resource.

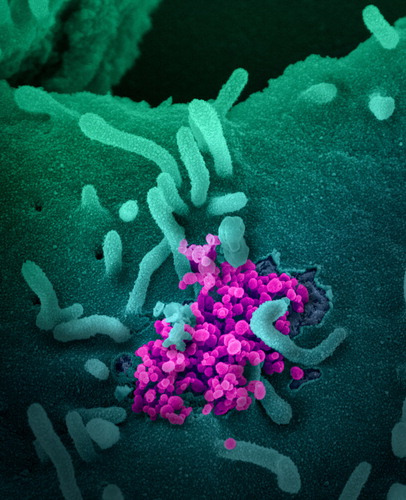

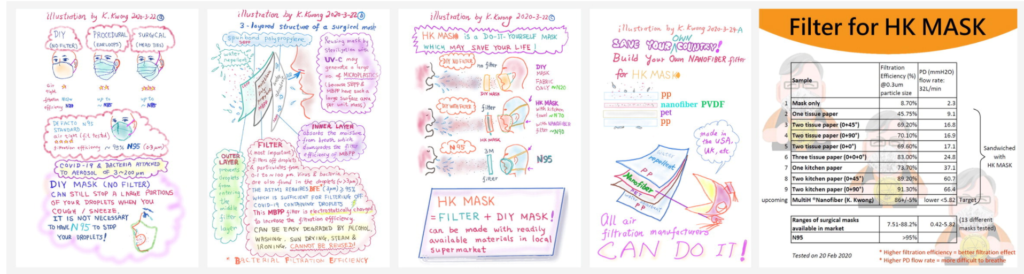

In its most direct way, a design lens during the pandemic follows things. It helps us see the flows of things and the obstacles in their circulation and distribution, who has and who does not have access to material resources, and how new configurations emerge in response to these deficits. The various shortages of not only PPE, but material resources in general, was one of the early results of the pandemic and an indication of the public health as well as socio-economic crisis that followed. These material shortages made obvious, even to those who had no problem with neoliberalism, that the weakening of the state can have disastrous results, and that the market is not going to spontaneously provide solutions to these problems. At the same time, this generated a new “designerly” production, material knowledge circulation, and distribution of resources that operated with a very different logic than that of the existing provisions. These were driven neither from the market nor from the state, but from people who were not participating in these realms of material production before. We saw people with 3D printers experimenting in the production of PPE and supplying these to health professionals. We also saw health care professionals designing new spatial configurations themselves (as discussed in my interview with Efie Galiatsou, an intensive care physician in London); we saw a huge amount of uncopyrighted mask-making knowledge being distributed widely on the web as a means of both protection and resistance (as discussed in Kyle Kwok’s dispatch from Hong Kong); we saw activists involved in mutual aid efforts, compiling and distributing material resources to vulnerable populations (Penny Travlou reporting from Greece); and we saw spontaneous care networks developed in ways that were more radical than those designed by professionals that were based not only on notions of risk and safety, but also on solidarity (as Júlia Benini, Ezio Manzini, and Lekshmy Parameswaran reported from Barcelona). A design lens helps us see the material changes in an environment, both those that are enforced from the top, and those that emerge through adaptations or people’s will to resist an enforced change.

A way that design work might be different from other approaches such as social sciences is that it is less “damage-centered” and more “desire-centered” (to use the terms of Eve Tuck), less about undoing problems and more about doing what is seen as desired, preferred, or improved. And in this optimism lie both its flaws and its potentials; flaws because the “solutions” are often alleviating symptoms and not root problems, and potential because they offer tools of empowerment and open new horizons of action.

Mark Frazier: As you noted in your introduction, the pandemic demonstrated the capacity for societies to make radical and sudden changes in daily practices, movements, and much else. Did the early responses around the world underscore the possibilities for making systemic changes to institutions and structures (racism, capitalism, climate) that we’ve heard for so long are not amenable to a “quick fix?”

What I think the special issue does very well is to offer a snapshot of the wealth of the imaginative and pragmatic interventions that creatively and critically are deployed to navigate our times.

Betti Marenko: We didn’t want to make grand claims, in particular we did not want to present definitive solutions to the huge and highly complex problems generated by the pandemic. Rather, our (situated, partial, localized) approach was to utilize these multiple ways of experiencing the challenges and opportunities of the pandemic, collected in the special issue, as a picklock of sorts, to interrogate existent fault lines, to ask questions that can help us reframe systemic problems into manageable (and situated, partial, localized) ‘designable’ interventions. What I think the special issue does very well is to offer a snapshot of the wealth of the imaginative and pragmatic interventions that creatively and critically are deployed to navigate our times.

Importantly, these images participate in another aspect that the special issue wanted to pay attention to: the shift in education and the myriad of new (or repurposed) strategies that had to be put in place and experimented with to continue working as educators, to continue teaching and mobilizing our community of students dispersed across many locations.

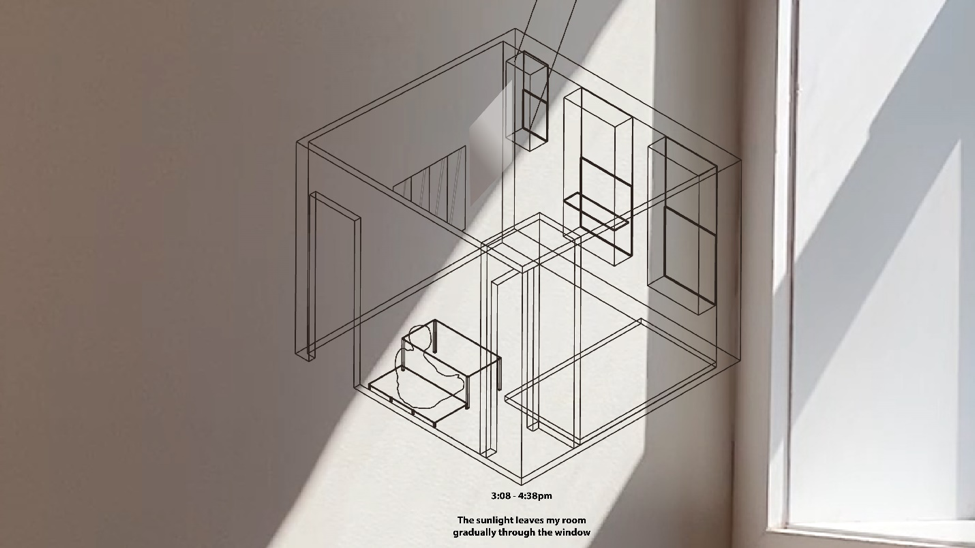

For instance, there is something which is both poignant, because of its relatable-ness, and inspiring, in the research conducted by the Observational Practices Lab whose Atlas of Everyday Objects captures vividly the shift in how objects co-participate in, and constantly mediate, the ‘design of the everyday’. The images collected globally represent an interesting experiment in observing and documenting this shift, through a distributed bottom-up initiative of recording the flows of affects that they express and the way their tangibility and proximity became charged with new unexpected forms of connection, sociality or alienation. Importantly, these images participate in another aspect that the special issue wanted to pay attention to: the shift in education and the myriad of new (or repurposed) strategies that had to be put in place and experimented with to continue working as educators, to continue teaching and mobilizing our community of students dispersed across many locations. In this sense the Atlas, together with Laura Belik’s account of the use of the radio in Brazil as the essential channel for educational purposes (and resistance), and Marcos Martins’ dispatch from his account of building ‘another type of class’ as a pandemic pedagogical experiment would resonate with the experience of many (not only design) educators. And of course, it was important to include the unfiltered voices of a group of students too (Emily Franklin & Lauren Suiter). Their thinking through their experience as a collective morass allows them to reorient losses and gains, together.

Mark Frazier: Many of your multi-media contributions highlight the micro-local experiences of the pandemic, the domains of “at home” and the “locked-down,” but perhaps paradoxically, also “worlding” from home. One photographer invents locations “São Paolo” and “Louisiana” on his walks in East London. Those with the resources to work and study from home using various video platforms communicated with colleagues, teachers, students around the world. Can you comment on the new materialities of the pandemic and how they have perhaps compressed global space and time, perhaps in permanent ways?

Betti Marenko: Talking about the new experience of “worlding from home,” we think our contributors have offered some inspiring trajectories using formats of multimedia scholarship, such as video, visual and audio essays (Glissmann & Kimball, Bastel, Yu). A lot of it has to do with a sort of enhanced attention paid to our immediate surroundings and how to mobilize them so that new kinds of encounters can become possible, and how new modes of existence can be enacted, experienced and practiced in the everyday. Bastel’s Corona Mornings photographs captured our attention precisely because of their declared intention to evoke an elsewhere that was, at that moment, as elusive as unachievable. They eschew the nostalgia trap expressed by the compulsion to “get back to normal” as soon as possible; nor are they simply evoking a dream state. Rather, they convey that collapse of the ‘here’ and ‘there’ contained in an experience that was both hyper-local and as global as very few others in recent memory.

As many of us continue to experience, and have remarked upon, this collapse of local/global and its material and technological implications might be one of the most salient and perhaps long-standing impacts of the pandemic. Last year’s forced turn to remote work accelerated existing tendencies, and while there are some undisputable benefits (we are avoiding unnecessary travel, checking our carbon footprint, and gaining wider access to cultural and research activities and events worldwide), we also must keep alert as to how these changes are conceptualized and practiced. The rhetoric of limitless connectivity, speed and technological prowess has a powerful hold on our collective imagination and expectations, but screen fatigue is real. When the whole world is filtered through a thirteen–inch screen, it is not only the horizon that seems to shrink, but also our capacity to reach out with empathy. To stay tuned to non-verbal nuances, ambiguity and tacit understanding (or misunderstanding!) requires huge effort and at times is simply impossible.

As an educator, what I quickly realized is that there is a big difference between, say, emergency teaching (which took place immediately after lockdown started in March 2020) and the demands of sustainable forms of remote learning and remote collaboration. If there is one thing that the past twelve months have made abundantly clear, it is that teaching and learning online is not and cannot be simply a matter of uploading the same content only onto a different medium/platform. Rather, it is an entirely different landscape that requires rethinking methods, fine tuning modus operandi, sometimes even the rationale behind initiatives, and certainly the modes of engagement required from the participants. Another aspect that we have barely started to address is the technocratic shift that is taking place through this forced reliance on digital platforms. On the one hand, this shift functions by an effective capture of the totality of human experience (time, attention, life world, affect) forcing users to adapt to the requirements of machines. One the other, it highlights in a strident way the impact of digital inequality worldwide and how this is yet another instance of systemic injustice.

Mark Frazier: As you say in your editors’ introduction, your aim was to use design perspectives to understand the “dramatically deepening systemic social and geopolitical inequities and new territorial divides” created by the pandemic. Can you draw some examples of this from your fascinating “collection of dispatches?”

These dispatches also show that in many cases the pandemic was a revelatory crisis, while in many places the pandemic was not the shock of the century, but an imbricated experience of ongoing crisis.

Jilly Traganou: Taking into account who can afford writing for an academic journal in the midst of the pandemic, it is pretty obvious that the majority of the people who were affected by inequities and divides would not be in the position to be our direct correspondents. What we saw however in the responses we received is that hearing and learning from such experiences became for many of the academic world a deliberate pursuit during the pandemic that re-directed their practices and research. Denise Milstein’s work with the Oral History Archives at Columbia was a rapid-response focusing on the documentation of the experiences of New Yorkers during the pandemic, especially the most vulnerable groups (Adams/Milstein). Belik’s dispatch on radio schools in favelas and remote rural regions of Brazil emerged from such an interest. Helena Krobath’s audio essay is the result of her work as an acoustic researcher who through deep listening realizes how social divides have altered her own environment. I believe that for many of the academics who were engaged with the pandemic as research this was not just an intellectual exercise, but a much deeper motivation to both comprehend and contribute, which for many included participation in mutual aid efforts and processes of organizing for political change. Travlou’s dispatch emerged precisely from such an experience, as an auto-ethnography of her involvement in Kropotkin-19, a mutual aid network in Athens that expanded the infrastructures of support that was originally created during the financial crisis that began in 2008. These dispatches also show that in many cases the pandemic was a revelatory crisis, while in many places the pandemic was not the shock of the century, but an imbricated experience of ongoing crisis.

Mark Frazier: There’s been a great deal of speculation about how cities and work in cities will look after the pandemic. How do the collections in the special issue help us understand disruptions and continuities in urban design, pre- and post-2020?

Jilly Traganou: When I think of my own urban experience in New York in the first months of the pandemic, my pandemic mental map was structured along lines of viral density and risk. What I was seeing was a new reconfigured urbanity defined on the one hand by distinct private enclosures of relatively protected places with limited, or rather controlled, physical connectivity to each other, and on the other hand by an amorphous, or difficult to clearly perceive, outside, where collective life and precariousness prevailed. In the first months of the pandemic there was also a lot of attention to the desertification of public space which was spectacularized by the media. But we soon realized that what was deserving of real attention were spaces of viral and human density, such as the Amazon warehouses, the meat industrial plants, prisons, elderly care facilities, hospitals, as well as neighborhoods where people could not afford staying at home.

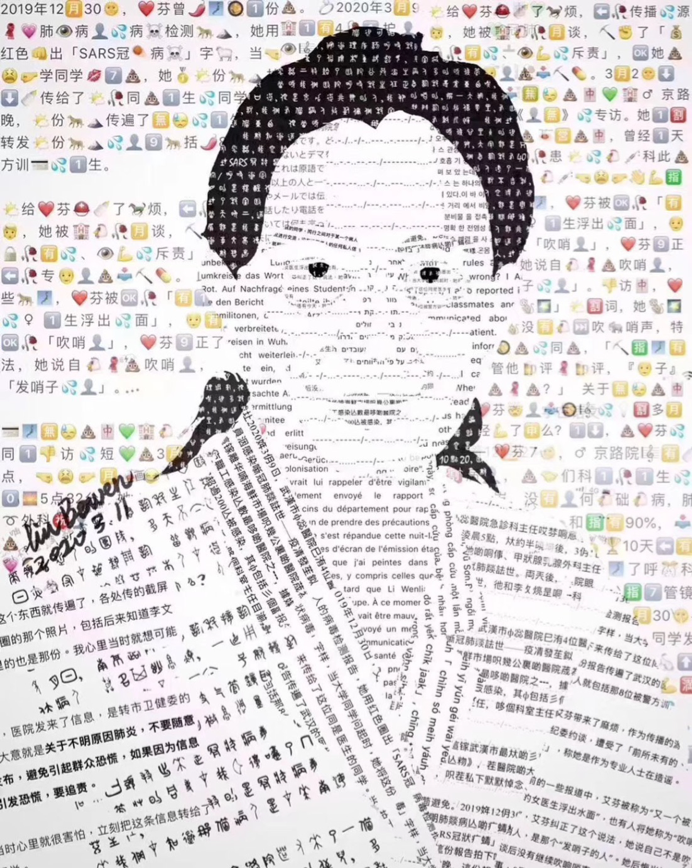

As Betti mentioned above, in the same period, we have the accentuation of “worlding from home,” mostly for those privileged to be confined at home as seen in our auto-ethnographic dispatches. But parallel to this we have people for whom home is not a safe haven, because they are homeless or at risk of eviction, because they have family members who are sick or at risk of becoming sick, or because they are experiencing domestic violence. Some of our dispatches hint at the realities of home as a liability. Our audio dispatch by Krobath, for example, listens to the sound of can-pickers on the street while almost everyone else is at home. And last, several of our dispatches examine actions that take place in the public realm, both physical and virtual, looking at acts that set up bigger political demands, resist various forms of oppression, and step in where there is a state deficit by rearranging the domain of the sensible and the materiality of life. We have three dispatches that discuss resistance in China, Hong Kong and Greece by Ruimin Ma, Kwok and Travlou respectively.

What we see happening a year after the beginning of the pandemic is that going back to life in enclosures will remain possible for those who can afford it. At the same time there is a persistence of collective life that cannot be contained by lockdowns especially in places where crisis is not new. Many questions remain regarding the future of the places of gathering for public life, which we saw both contracting and expanding at different moments of the pandemic, and the role of monopolies in the rearrangement of infrastructures and distribution, with private companies like Amazon, Microsoft, or Zoom having acquired enormous power. These are of course inherently political questions, but many of their aspects demand technical re-configuration and thus design plays a huge role. Design and politics are in my mind the arts of the possible but we should not assume that there is a direct relation between them. What would be a democratic design in response to the pandemic is often very unclear and debatable.

Dr. Betti Marenko is a transdisciplinary theorist, academic and educator working across process philosophies, design studies and critical technologies. She is the founder and director of the Hybrid Futures Lab, a transversal research initiative developing speculative-pragmatic interventions and future-crafting practices. She is Reader in Design and Techno-Digital Futures at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London and WRHI Specially Appointed Professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology.

Dr. Jilly Traganou is Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at Parsons School of Design, The New School. She is the editor of Design and Political Dissent: Spaces, Visuals, Materialities (Routledge 2020), co-editor with Miodrag Mitrasinovic of “Travel, Space, Architecture” (Ashgate, 2009); and author of “Designing the Olympics: Representation, Participation, Contestation” (Routledge, 2016), and “The Tokaido Road: Traveling and Representation in Edo and Meiji Japan” (Routledge Curzon, 2004). She is co-editor on chief of Design and Culture together with Barbara Adams and Mahmoud Keshavarz. In 2020-21 she was GIDEST fellow working on the role of material engagement in prefigurative politics.