By Ruilong Zhang, 25/8/2023.

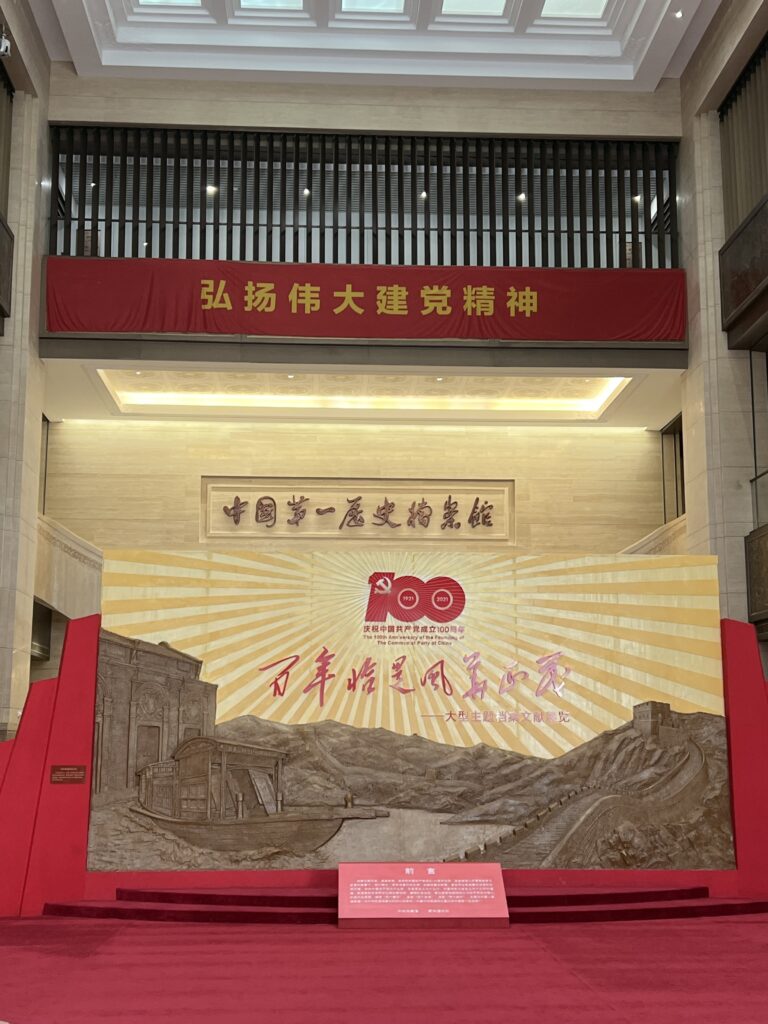

Since Imperial China was too large to be managed by only one person, the emperors had to share their ruling power with a huge bureaucracy. Therefore, how did Chinese emperors ensure their commands were accurately implemented by bureaucracy, and how the information emperors received was truth instead of lies? My research project, which focuses on the role of the supervisory system in Imperial China’s politics with special attention on the Ming and Qing dynasties, helps to answer the question above. It explores that how the emperors of Ming and Qing built a nationwide supervisory system and utilized its officials to oversee the whole bureaucracy. To better understand the real function of Ming and Qing’s supervisory system, I visited the First Historical Archives of China (FHAC, 中国第一历史档案馆) in Beijing and viewed the officials’ memorial to the emperor from the supervisory system.

Firstly, I want to share my research experience at the FHAC. It is a must-go place for scholars interested in the Qing dynasty’s central government. The FHAC provided a very comprehensive collection of archives from Qing’s central government, and documents are available for readers to view only in digital versions. For Chinese citizens, the visit appointment can be easily made through an app in WeChat called 中国第一历史档案馆 (FHAC).

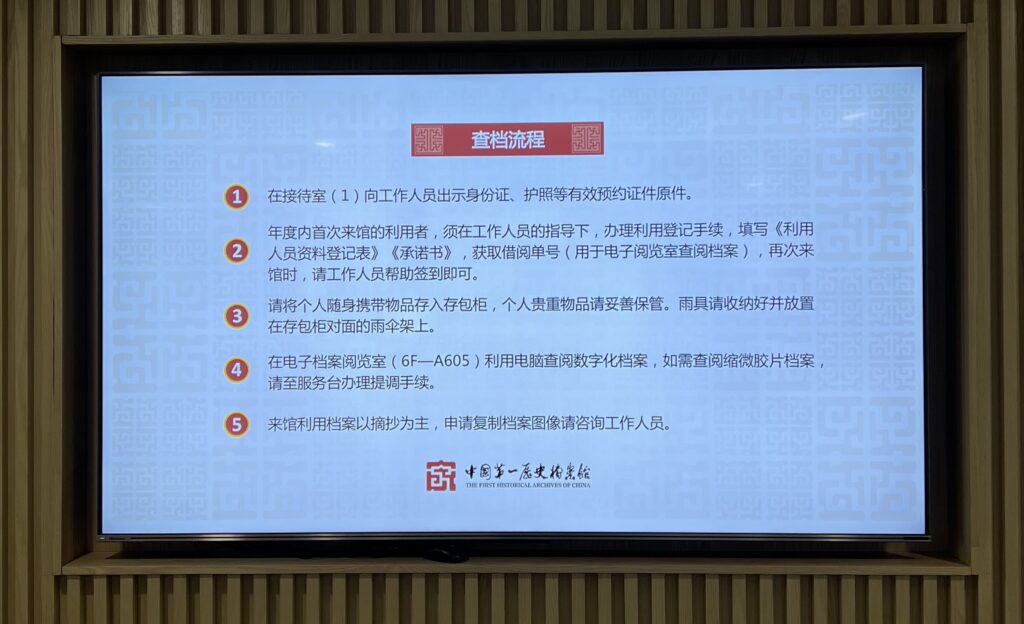

For the procedure of archival research check-in and rules, please see the picture below.

The staff there are nice and helpful. If you plan to visit here, you can do some preparation on FHAC’s website. Its online research portal allows you to search keywords among the documents and save the document number. This would save you time on site. The online research portal is shown below.

At FHAC, I was assigned a unique number and a computer to do my research. The unique number is my ID at FHAC, which is required to log into the FHAC’s computer and view archives. In the viewing room, photography is not allowed. I can only write down my findings.

Secondly, I want to give readers a sneak peek of my FHAC research findings here. One of the most interesting documents that I viewed at FHAC is the reply from Emperor Yong Zheng (雍正) to an incident brought by Vice Chief National Supervisor Wu Longyuan (都察院左佥都御史,吴隆元). As a chief member of the supervisory system, Wu submitted a memorial to report two critical military generals, Long Keduo (隆科多) and Nian Gengyao (年羹尧), who corrupted and lied to Emperor Yong Zheng. Long Keduo and Nian Gengyao are so influential and powerful that almost no one is brave enough to go against them. Thus, Wu’s memorial to Yong Zheng triggered one of the most significant political chaos in Yong Zheng’s era. According to the archive, Wu’s memorial was submitted on May 15th, Yong Zheng Third Year. Yong Zheng didn’t reply to Wu’s memorial but only replied to one memorial on this incident, submitted in the name of a group of chief officials on May 24th, Yong Zheng Third Year, nine days after Wu’s report.

The group memorial expressed their enormous anger after knowing Long Keduo and Nian Gengyao’s corruption and their appreciation for Yong Zheng’s mercy to forgive Long and Nian. Yong Zheng’s reply to this group memorial said: “My fault, I know, I corrected it…These are my words. From today to the past, if anyone has made similar mistakes, please also correct them; if you didn’t make mistakes, please warn yourself. I, as an emperor, and you, as chief officials, this is a lesson for us.” (朕之过,朕知,改矣…是朕谕,自兹以往,有则改之,无则加勉,我君臣交相警诫了也。)

In 1957, Mao Zedong once discussed about Ho Chi Minh’s self-criticism in a meeting, “Emperors should not admit their faults at all. If they admit their faults, the empire will collapse.” I was surprised that Yong Zheng did admit his fault in front of officials. And an emperor even could admit his fault in a written format. In addition, even though Yong Zheng was the emperor, which granted him supreme power, I was surprised again by how cautious Yong Zheng was when dealing with corruption and how careful his bureaucracy was when responding to Emperor Yong Zheng.

I am still organizing the notes I made during the archival research at FHAC and my other notes from related scholars’ publications. And I want to thank Indian-China Institute again for sponsoring my research. I look forward to sharing more findings in my future presentation at the Indian-China Institute.